The thing I love most about my work? The people. Time spent in TV, radio and publishing has afforded me a very special privilege: I’m allowed to get under the skin of the most extraordinary of people. What they have accomplished in life is of course interesting, but what really fascinates me is the psychology underpinning their achievements. Be it the refusal to conform, or the will to win – those are the magic ingredients, the dots to join in shaping a blueprint for success.

The thing I love most about my work? The people. Time spent in TV, radio and publishing has afforded me a very special privilege: I’m allowed to get under the skin of the most extraordinary of people. What they have accomplished in life is of course interesting, but what really fascinates me is the psychology underpinning their achievements. Be it the refusal to conform, or the will to win – those are the magic ingredients, the dots to join in shaping a blueprint for success.

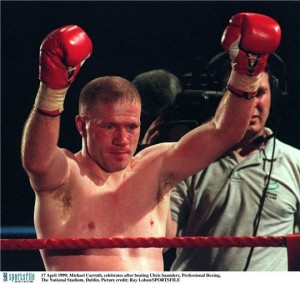

Boxing is not my strongest subject, but Michael Carruth’s is a name I know well. Michael – who in 1992 won Olympic gold in Barcelona – was the man who brought a nation to its feet as his hand was raised aloft, victorious. He is the man who, while a relative underdog, won Ireland’s first Olympic gold medal since 1956 (and no other Irishman has claimed gold since). The world has laterally come to perceive Ireland as a crucible of boxing excellence – thanks in no small part to the inimitable Katie Taylor – but it was Michael Carruth who put us in the ring.

When we meet, I want to learn more about those magic ingredients – his family, upbringing and talent – that conspired to create a world-beating athlete. By our conversation’s conclusion, however, I have come away with a more intriguing piece of information still: in order to succeed, Michael Carruth needed to fail first.

Born in the South Dublin suburb of Drimnagh, Michael was one of Austin and Joan Carruth’s ten children, and a triplet to boot. His father, a carpenter, fashioned a three-unit crib for the triplets, meaning little Michael was fighting his corner, quite literally, from day one. ‘From the very start we were into boxing, even if we didn’t realise it! Dad was said there was great competition between us in the crib, and it was great for him to watch.’

It helped that Dad was one of the country’s most respected boxing coaches, and it was in fact through the sport that Michael’s parents had met. ‘My Da boxed for St Francis’ Boxing Club down on Usher’s Quay,’ he tells me. ‘My mother’s father was one of the chairpeople of the club…and her brothers, my uncles, boxed there. My uncle Martin Humson was the first light-middleweight champion of Ireland. So my Da was hanging around with the Humson lads when he discovered they had a pretty sister…it went from there.’

With the home support team firmly in place – even if Joan could rarely bear to watch her son compete – honing his craft came next. Here’s where Michael had an advantage: while other kids searched to find suitable sparring partners, his ideal opponents came ready-made in the form of his brothers, Martin and William. ‘As a triplet, when you get into the ring with one or the other of your brothers, there is no fear there,’ he explains. ‘So we would absolutely leather each other, and my Dad had to pull us out of the ring more times…’

This was the best kind of competition: the kind where each individual pushes to the last, a healthy rivalry where not physicality alone but a winner’s mentality ensured the edge. As Michael puts it: ‘I suppose the beautiful thing was that we really did help one another. You never wanted to lose face against one of your brothers, so you got that inner toughness and the will to win. That’s what drove me on to be as good as I was. I always had that belief in myself that I could win.’

The stars continued to align as, on leaving school, Michael opted for army life. This was a defining move, as once again his passion was met with considerable support. ‘I won an Irish boxing title within a few weeks of joining the Defence Forces,’ he recalls. ‘They saw the potential in me and so they kept me in the gym, allowing me to train while holding down my army job at the same time.’

His employers’ patronage notwithstanding, Michael’s Olympic ambition was such that potential obstacles existed merely to be overcome. ‘It was always my dream,’ he tells me. ‘I remember watching the Olympics when I was eight years old. I had just started with Greenhills Boxing Club at the time; had won my first match. I came back into the corner and the very first thing I said to my Dad was, ‘I’m going to win the Olympics.’ He looked at me like I was a madman. But he made me promise I’d do it, and so I promised.’

Seventeen years later, the world would watch as Michael Carruth leapt high into the air and directly into the arms of his elated father, his mentor. An eight-year-old’s promise would be fulfilled in that moment … but it had not arrived yet. Before Barcelona came the Olympic Games in Seoul, 1988. The news landed, courtesy of his father, on a typical Sunday afternoon: Michael had been selected to compete at sport’s highest level. The dream was edging ever closer to reality. The reality of Michael’s experience at Seoul was, however, the stuff of nightmares. He made, in his own words, a ‘dog’s dinner’ of the competition, losing out in a second-round match commentators agreed was his to win. The reason? A superhuman sportsman had behaved like a very human twenty-one-year-old guy.

‘What went wrong in Seoul is that I got caught up in emotion. There was a lot of signing autographs, and meeting famous people…I took my eye off the ball and got beaten in my second fight.’ It was the classic case of pride coming before a fall, I suggest, as Michael tells me that failure was his greatest teacher. ‘It was the best experience I’ve ever got in my life – believe it or not. I just said to myself, this ain’t gonna happen again, and if I can right the wrong of Seoul, I am absolutely going to.’

Four years is a long time to wait, and no more so than in an arena where peak physicality is the premium. Four years of criticism for past failures, too, is endemic to an Olympian’s life. Michael had two choices: believe his detractors and bow out, or rebuild his objective, now armed with the wisdom of what not to do. His mother, he confides, was hugely influential in his selection of the latter choice. ‘She was there when I lost, when I wouldn’t know what to do. She’d give me a cuddle and say, ‘you’ll get him back the next time’. After Seoul she said, ‘it wasn’t your time…it will be the next.’ I was just so disappointed with my failure, but my Ma got me back on the bike as it were, saying little things like, ‘I know you’ll come good…’ And she was the first one up the steps to congratulate me in Barcelona…she bumped everyone out of the way, including my wife, Paula! She was a great woman, and she always made me believe in myself.’

Cometh the hour, cometh the man: the year was 1992 and Michael Carruth was primed. His father Austin, meanwhile, was leaving nothing to chance. ‘I called him my tormentor, rather than my mentor,’ Michael has said, recounting how his Dad would wake him in the middle of the night, dispensing water to allay any risk of dehydration. Before the Olympic final, Austin told his son not to be the aggressor, but to ‘keep it together’ – a line repeated mantra-like from the corner as the Dublin lad of five feet, seven inches, took on the might of then world champion, Cuban Juan Hernández, standing tall at six foot three. I ask if Michael can recall how he felt, just as the first-round bell was about to sound. ‘I had a sneaky feeling I would win actually. A gut feeling – we boxers tend to be superstitious – and all the omens were looking good to me. I also knew I was in the best condition of my life.’

Nine relentless, bruising minutes later, and that famous jump flashed into homes across the planet – ‘Thank God the ropes were there because I would have done damage to myself otherwise…’ The underdog had triumphed, and he scarcely needed a referee’s confirmation. ‘I knew by Hernandez’ reaction that I’d won it,’ Michael says. ‘And it helped that there were around five or six hundred people in the arena for me that day, too…we were all waiting for that moment.’

Watching that historic moment raises goosepimples even now. ‘I was remembering that promise I’d made to my father some seventeen years before. I went over to him, hugged him, and he said, ‘thanks’. I said, ‘for what’? ‘For keeping your promise.’ That made it even more special.’

An intimate exchange was to prove the precursor to a massively public outpouring of pride. ‘My Dad never was Flash Harry,’ Michael reflects. ‘After the match he put my gold medal into a dirty sock for safekeeping. I think it was his way of saying: just because we have it, doesn’t mean we should walk around like peacocks showing it off.’ Ireland, of course, had other ideas. ‘We were returning from Barcelona at one am on a Monday morning, and Dublin airport was stuffed full of people; thirty to forty thousand well-wishers. Next, we’re driving out of the airport, and there are thousands of people lining each side of the road…it was absolutely crazy.’

In the eye of euphoria, Michael again looked to family for stability. ‘My wife Paula and the rest of my family were trying to prepare me for what was going on. Because remember, I went out to Barcelona as a nobody in a sense…and all of a sudden I’m going into this microwave of fame…that’s how quick it was.’ His wife, his siblings – ‘always quick to put me back in my place’ – and experience ensured fame rested easy on Michael’s shoulders this second time around. ‘I mean, with an Olympic title they can never take it away from you, you’ll always be the person asked for an autograph by a kid in the street. But it’s very important to have those days where you don’t take yourself too seriously. The bottomline was that it was just another fight. I’ve had ups and downs in my life, and I know that winning a gold medal is not the most important thing there is.’

I ask for his meditations on what matters more than gold. ‘Family,’ is his immediate response, as he talks fondly of his parents, each of whom has passed away in recent years. ‘They started dating at fourteen years of age and spent fifty-four lovely years together,’ he tells me, ‘before my father passed away in 2011, and my Ma in 2013. It’s been a tough thing for the family, but we’d like to think that they’re back together now.’ He also mentions a nephew, tragically lost to an accident at the tender age of eight. ‘Gary drowned in Blessington Lakes in 1989. That was a terrible low. His death had actually been a true inspiration for me to achieve in boxing…I would push myself even harder, for the little fella. Would I have given up my gold medal to have Gary back? In a heartbeat.’

Michael now paces the ropes, as his father before him, putting young boxers through their paces. ‘I’m there seven days a week…it’s my passion.’ I wonder if this Olympic hero ever lets the next generation cut him down to size. ‘They do and they don’t, Norah,’ he smiles. ‘I’m the boss…but the beautiful thing is that I have so much inside myself that I can give back out. My father gave it all his life, and every boxing coach in the country does the same. My own son, Carl, starting boxing only last year. He’s doing well, a little southpaw like his Dad. He’s crafty, but he has a bit to do to catch up!’ Michael and Paula are also proud parents to a daughter, Leah, but my suggestion of a Katie-Taylor-in-waiting is swiftly dismissed. ‘No, Leah is an aspiring actress…she jokes that when she gets her first Oscar, she’s only going to thank her Daddy, and not her Mammy! That’s because her Mammy tells her to cop on and get a proper job, but I tell her to chase her dreams.’

Michael Carruth continues to dream, cognisant that every dream may not be realised. A man of few regrets, he concedes that his post-Olympic boxing career might have taken on a different hue. ‘All of a sudden, at twenty five, I had won the greatest prize of them all. People were saying, don’t go to the next Olympics, because if you don’t win, it will take away from the last one … but don’t turn professional either. So I’m thinking: you’re telling me to give up the thing I love most – apart from family, of course. And I wasn’t ready to give up boxing. My only option was to turn professional. I thought, now’s the time to make some money for myself, see if I can set myself up for life…’ A lack of funding and the inherent volatility of athletic performance combined to make Michael’s professional boxing career less stellar than that of amateur years. The upshot, however, is a man now pursuing a vocation: to provide others with those magic ingredients he had been so fortunate to receive.

We say our goodbyes; Michael leaving me with a very honest, perfectly fundamental account of what international acclaim has meant to him.

‘Success like mine is something that changes your life, initially. I mean, ‘Carruth’ was always a name that people got wrong. They’d call us anything from Carruthers to Carrots or whatever…and one thing my grand-da said, at 89 years old, was, ‘at least they’ll get our name right now’. So if I’ve done anything in my life people know my name is not Michael Carrot! My name is Michael Carruth.’